Global policy trends from Western countries- because they provide most funding and occasionally intellectual heft, have a way of becoming fashionable elsewhere, their merit in the local setting notwithstanding.

Even when the said policies are discredited in Western countries where they originate from, they have ways of being rehabilitated and accepted uncritically in the Global South.

CVE is one such trend that has grown into a cottage industry, and in the process, everything has become CVE, with everyone turning into an overnight CVE “expert.”.

While CVE initially emerged as a response to the counterproductive consequences of Counterterrorism, in time, it has morphed into a banality hollowed out of its utility, meaning, and potency.

For a start, attempts at extracting a working definition from the CVE “experts” induces the insufferable consequences of the unguarded echo chamber of word salad with push-pull being the pick of the bunch, always thrown around with relative abandon enriching the ever-growing fancy-sounding but unhelpful CVE lexicon.

From CT-CVE

In Kenya, since intervening in Somalia in 2011, Al Shabaab made Kenya a bona fide target. This was accompanied by an increase in Al Shabaab attacks inside Kenya targeting both hard military targets and soft civilian targets.

In response, Kenya instituted a raft of legal, policy and administrative move; the parliament passed the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA), established Anti-Terror Police Unit (ATPU) and broadly escalated targeting alleged terrorist suspects.

As part of that, In Muslim majority areas, coast, Northern Kenyan and parts of Nairobi, security agencies started committing egregious human rights violations-extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, torture, etc., especially ATPU in the name of fighting terrorism.

Human rights groups documenting government agencies’ violations were also targeted through legal and bureaucratic suffocation, this paralysing their daily operation. This included closing their offices, taking away their computers, using Kenya Revenue Authorities to question their tax compliance and freezing of their bank accounts.

This generated an outcry from communities and their leaders.

Hence Kenya’s pivot alongside other countries to pivot towards CVE. This was in line with the global shift in the discourse regarding the utility of Counterterrorism as a tool for fighting the rising tide of domestic terrorism; it was no longer a threat emanating from far off countries, but it’s homegrown.

However, the remarkable aspect of CVE’s “trendiness” is none of the diagnoses is hardly original. Still, they are instead a laundry list of repackaged solutions that are dusted off the shelf.

Some have been borrowed from Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) or disarmament, demobilisation, repatriation, reintegration, and resettlement. the sameness of change without context; the canned repetition of the same interventions

The Danish Model

Prevention of terrorism became a top item on Denmark’s political agenda in the wake of the murder of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh in 2004, the bomb attacks in Madrid in 2004, and the bomb attacks in London in 2005. This combined with the Danish daily Jyllands-Posten’s printing of twelve cartoons of Prophet Muhammad wearing a turban shaped like a bomb, with a lit fuse, in 2005.

Kwale, Lamu and Mombasa counties county CVE plans were heavily borrowed from the Danish Aarhus Model, named after the Aarhus region. The model was developed when in 2009, the Danish Ministry of Refugee, Immigration and Integration Affairs was given EU approval for a 3-year pilot project on deradicalisation. The project was launched in cooperation with the municipalities of Copenhagen and Aarhus, East Jutland Police District and the Danish Security and Intelligence Service (PET), the Ministry.

The model also works at three levels; General, this level is about raising awareness through public information programs. Specific this level involves those identified as individuals or groups who are planning to travel to join extremist groups. Targeted level, this intervention is designed for individuals and groups who are considered “imminent risk”. Activities at this level involve exit and mentoring programs.

Further, the Danish CVE plan is a multi-agency affair involving the Danish Security and Intelligence Service Centre for Prevention, Ministry of Immigration, Integration, and Housing, and Danish Agency for International Recruitment and Integration. The Danish approach draws on decades of experience with similar collaboration from other areas and benefits from already existing structures and initiatives developed for other purposes than specifically preventing extremism and radicalisation.

However, adopting the model wholesale without considering the local peculiarities of Kenya misses the point that what works for Denmark does not necessarily work for Lamu, Kwale, and Mombasa. The biggest challenge in adopting the model in Kenya is, there is no national legal-policy framework regarding disengagement and reintegration of the returnees, a third element of the Aarhus model.

In April 2015, following the Al-Shabaab attacks at Garissa University, Cabinet Secretary, Internal Security and Coordination of National Government, Joseph Nkaissery, declared an amnesty for members of Al-Shabaab aiming to return to Kenya. According to Nkaissery, the amnesty was to “encourage those disillusioned with the group and wanted to come back.”

Under the amnesty, those who returned were to receive protection as well as rehabilitation and counselling. The program claimed that it would support training and alternative livelihood methods through work with different government ministries.

The amnesty, first announced in April 2015, was for an initial 10-day period. It was extended by two weeks. In May 2015, the government stated that 85 youths had so far surrendered under the amnesty program and that “the government had put in place an elaborate comprehensive integration program to absorb those who had surrendered.” A year and a half later, in October 2016, the government made the amnesty indefinite.

However, despite these claims and reports of anywhere from 700 to 1,000 fighters have returned from Somalia, the government has not been transparent in where the rehabilitation centres are or even the impact of the amnesty.

In the main, amnesty remains an announcement by the Cabinet Secretary and a press release. Because of the absence of policy, there is no identifiable government agency with which the amnesty sits. Further, Al Shabaab has been targeting the returnees because of desertion. This legal, policy and administrative gaps make all the plans designed by the counties mute.

Proper diagnosis.

One of the aspects that the County CVE plans got right, because of the diversity of the stakeholders involved and consulted, broadly, the plans have a sound analysis of issues that could predispose young men and women to be radicalised and eventually join violent extremist groups. The fact that local civil society organisations spearheaded discussions regarding the development of CVE plans also enhanced taking on board nuanced local realities. This also engendered legitimacy and trust from the communities.

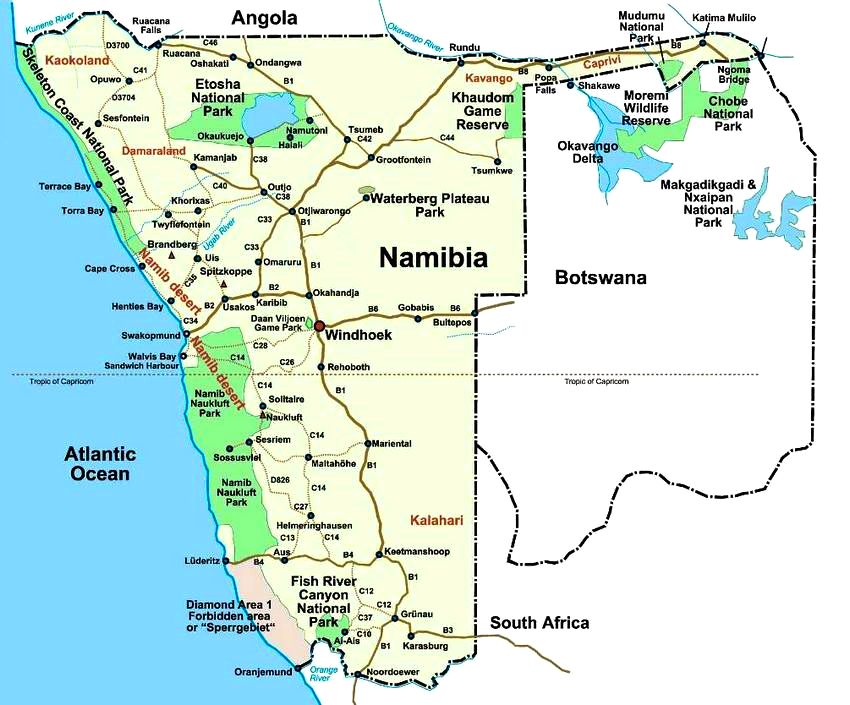

In the case of Kwale, the hotspots identified were Pandanguo Basuba (Kiangwe, Bauri, Mangai), Boni Forests, Pangani, Gamba, Milihoi, Bargoni, Hash-Bodhei junction, Mpeketoni, Amu, Witu, Kiunga, Faza, Pate, Siu, Dar es salaam Point in Kwale, Diani, Ukunda, Kona Ya Musa, Bongwe, Mbuwani, Tiwi, Ngombeni, Kombani, Mwapala, Matuga, and Lunga was identified as the hotspot areas. Majengo, Kisauni, Old Town, Bondeni and Likoni, especially Majengo Mapya in Mombasa, was identified as the hotspot areas.

The two aspects that have not been fully fleshed in most of the plans are the source of money in implementing the programs—for instance, the Mombasa County Action Plan budgeted for 430,223,000 for January- December 2018. However, the available funds were 128,000,600, 29.77%, which represents a 70.23% deficit. Second, the importance of women, while mentioned, has not been addressed in detail. This arises from the assumption that violent extremism is primarily a men’s domain.

Fighting violent extremism is a highly challenging undertaking but uncritically exporting solutions without customising them for local realities, and besides, without considering their utility in addressing the problems at hand. In the UK and the US, CVE has been discredited because it was primarily surveillance on an industrial scale of communities. But because it’s benign-sounding albeit insidious, underwritten by the donors and willfully accepted by the state. The actual test of CVE should be measured not in the cottage industry of consultants and organisations it has spurred but rather an empirical examination of its utility based on the local realities.